Button hole machines-"Looking in the Keyhole"

Grace Rogers Cooper’s Book The Sewing Machine, Its Invention and Development, traces the development of stitching buttonholes by mechanical means. She stated that 1854 marked the first patent of a machine that was built to sew buttonholes. Charles Miller was the inventor of this "whip-stitched buttonhole stitch". The stitch was very similar to our modern zig-zag stitch. She goes on to state that a buttonhole attachment was patented in 1856. In order to make the buttonhole; one merely attached this to a standard machine. However, since there seems to have been more of a desire to be the first on the market with the new product than producing something of lasting value, it was mechanically lacking. Several years after the close of the War, this very design was modified, and functioned quite well.

Frank P. Godfrey in his International History of the Sewing Machine, ISBN 0 7091 9876 0, mentions a machine which was invented in 1860, and was little more than a modified Singer flat bed type. It featured an attachment that allowed one to move the fabric from side to side to create a zig-zag pattern. As one would imagine, it would be virtually impossible to keep the stitches uniform, which made the attachment difficult to control, if not outright unreliable. Consequently, the machine could do little more than plain sewing.

Mr. Godfrey goes on to mention two other patents for buttonhole machines in 1860. Jacob Steiner designed a machine which produced an overedge stitch, made of two threads. Although it produced a beautiful stitch, the machine itself was too intricate, making operation very difficult. The machine was very difficult to maintain, and prone to breakage of the delicate parts.

Mr. I.M. Rose patented a machine in the same year, which was considered to be a buttonhole machine. In practical application, it was more of an overedge machine, which is to say, the kind of stitch that one finds binding the edges of blankets. It was a very clever design, but once again, very delicate.

All of above machines could not imitate the stitch found on the buttonhole. It was dependent upon the operator to move the machine around the opening in a consistent manner. Needless to say, although it was faster, it was considerably more difficult to make a consistent buttonhole. These were not "automatic" machines, where you pushed one button, and the machine made the buttonhole for you. You had to place each mechanical stitch manually.

David Wood Green Humphrey patented a machine on October 14th, 1862, (patent number 36, 617) for overedge and buttonhole sewing. The machine itself was designed in 1859 by Kasmir Vogel. In Ross Thompsons’ book The Path to Mechanized Shoe Production in the United States, he states that

"Vogel was a machinery manufacturer and designed an attachment that could stitch over the edge, Humphrey, working as Vogel’s bookkeeper, recognized that a specialized buttonhole machine was needed (and) patented such a machine in 1862..

His machine was very advanced and had many of the principles still used in modern day buttonhole machines. Thomson states

"(that) an automatic feed was constructed by securing the cloth to a rotating worktable which moved the cloth straight for the length of the buttonhole, rotated the cloth around the point of the buttonhole, and the progressed down the other side.

On August 3rd, 1864, he modified the machine with clamps to hold the fabric in place. His patent states "the portion of the cloth in which a buttonhole is to be worked, is first prepared by cutting a slit in it of the required length, with an eyelet at one end. It is then placed in a clamp consisting of a top and bottom clamp, having the general form of a buttonhole, but of larger dimensions. You could manually set the length of the buttonhole and the machine would automatically stop. He made other modifications for the patent granted on March 20th 1865. However, Thomson states that

"The machine achieved significant success, but not as the product of the Union Buttonhole company, Singer arranged to manufacture and sell the Union machine, and improved it, and finally bought Union Buttonhole in 1867".

The number of buttonhole machines produced by Singer was not provided, making it quite difficult to determine the impact on the garment industry. Mr. Godfrey stated that two of Mr. Humphrey’s machines are within the holdings of the Smithsonian Institution.

Thomson also mentions a buttonhole machine patented in 1862 by James and Henry House of Brooklyn New York. The firm of Wheeler and Wilson purchased these rights to this machine and retained the services of Msrs. House. Thomson states that

"an operative with two assistants to finish the ends could sew 1,000 buttonholes in a day, far above the 40 that could be done by hand. The Houses also designed an attachment for making buttonholes on family machines that Wheeler and Wilson considered to be its most important attachment."

After the close of the war, there were some other attempts at making buttonhole machines, but they, in the words of John Reece, "did not fill industrial requirements." John Reece was the  inventor of the machine, which has set the industry standard, which we also use here at Historic Clothiers. Mr. Godfrey states that there were "eighteen patents between Humphrey’s 1862 patent and John Reeces’ patent of 1881, all of which were for straight buttonholes, and none of which satisfied the needs of the industry".

inventor of the machine, which has set the industry standard, which we also use here at Historic Clothiers. Mr. Godfrey states that there were "eighteen patents between Humphrey’s 1862 patent and John Reeces’ patent of 1881, all of which were for straight buttonholes, and none of which satisfied the needs of the industry".

In 1882 John Reece patented the first automatic buttonhole machine, which was capable of making a consistent buttonhole without the operator manipulating the fabric. It actually cut the keyhole and sewed around the edge and very closely imitated the hand stitch. It also laid a gimp inside the stitch, which again was a feature of hand made buttonholes. He founded the Reece Buttonhole Machine Company in Boston, which produced the machine that is used by the garment industry to this day.

|

It wasn’t until twenty years following Humphrey’s 1862 patent did a fully functioning buttonhole machine come to fruition. During the Civil War period, the buttonhole machines were very difficult to run, and often gave inconsistent and poor results. As there are no solid numbers of manufacture, it is therefore very difficult to document the impact of the buttonhole machine on Civil War uniform production. Doubtless, there were garments made during the war with machine buttonholes, but the numbers were still eclipsed by those made by hand.

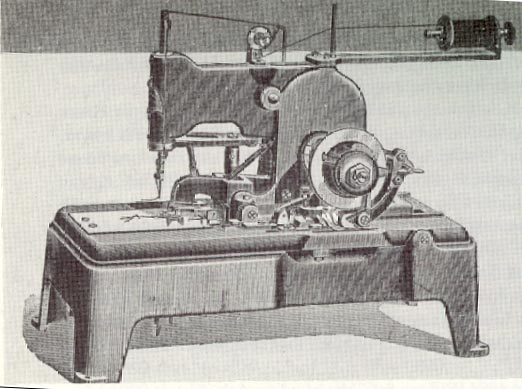

The machine pictured on the left is the Harris buttonhole machine. (circa 1880) This machine was an improvement of the 1856 patent.

The machine pictured on the left is the Harris buttonhole machine. (circa 1880) This machine was an improvement of the 1856 patent.